In the 1870s, astronomer and meteorologist Cleveland Abbey undertook a citizen science project to map and understand the aurora borealis observed at the North Pole. Volunteers scattered across the United States recorded this phenomenon from their local times, making work nearly impossible, but it was these difficulties that inspired the creation of modern time zones.

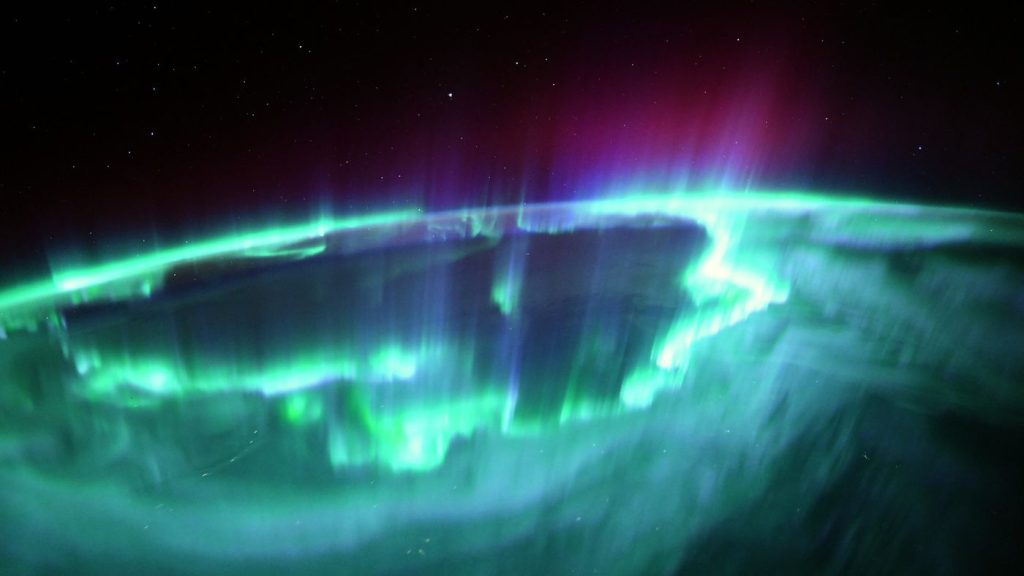

Thousands of years ago, mankind witnessed the colorful lights shining over the skies of the North and South Poles. Today, we understand how this phenomenon is produced and behaved, but in the nineteenth century, this mild symptom was a great mystery of nature.

In 1870, Cleveland Abbey devoted himself to understanding the aurora borealis. He is considered the “father” of the US Meteorological Service, providing the first reliable reports in the country’s history. In April 1874, she had the opportunity to study these northern lights after a solar storm.

Want to stay up to date with the latest tech news of the day? Access and subscribe to our new YouTube channel, Canaltech News. Every day a summary of the most important news from the world of technology for you!

The aurora borealis is the result of the influence of the solar wind with charged particles from the Earth’s magnetic field. When these particles reach the upper atmosphere, they begin to emit colored lights in ways that characterize this phenomenon. Abe wanted to know the altitude at which the aurora borealis occurred, and thus compare this information with other weather phenomena—but to do so, she needed to collect these observations from various points across the country.

Citizen science and timezone

So Abe assembled a team of 80 citizen volunteers and 20 experts, making his project one of the first examples of ordinary citizen collaboration in scientific research – well-known citizen science, which is now widely used in many works.

Despite the great contribution of volunteers, and a team of 100 people, the project ran into difficulties. Each observation was timed to local time, making it nearly impossible to draw useful conclusions from observations of the aurora borealis.

Abe then worked with the American Standards Society (AMS) to find a solution, until mathematician Benjamin Pierce proposed dividing the country into a series of time zones. Years later, Abe received a letter from railroad engineer Sandford Fleming, who also sought to standardize time.

Together, Abe and Fleming presented their ideas to the US Congress, calling for time zones to be formally established in the United States. Railroads came first in November 1883. A year later, an international conference defined the Greenwich Meridian Line.

In the following decades, other countries adopted time zones based on the meridian. In addition to its contribution to time synchronization at different points in the world, Abbe discovered that the aurora borealis occurred at an altitude of 100 km to 300 km.

Source: Via universe today

“Hardcore beer fanatic. Falls down a lot. Professional coffee fan. Music ninja.”

More Stories

China releases the most complete geological map of the Moon; look at the pictures

Registration is now open for the third cycle of the Science for All Prize

Sonaka workers win improvements to their health plan